I'm Getting Engaged!

A fundamental challenge of running a business is balancing between boosting demand and raising prices. Firms that offer digital services—even those that don't charge a direct price—must play a similar balancing act between boosting engagement and taking selfish actions that, akin to raising prices, negatively impact users:

- Higher ad fill rates earn YouTube more money but reduce engagement.

- Streaming AI music reduces licensing fees for Spotify (yes they do this [2]), but also reduces usage.

- Addictive content in my Instagram feed increases my tapping but reduces engagement in the longer term (at least I hope [3]).

What can we say about the incentives of such firms? Can we understand these engagement trade-offs similarly to how we reason about price-demand trade-offs? This blog provides some high-level answers.

Variable Interest Rates and “Experience Prices”

The digital services we’re interested in fall beyond the assumptions of classical pricing theory, which typically assume that a shopper can see the price of an item before buying it. But users don’t presciently know how many ads they’ll be shown when choosing whether to open an app; they’ll just use it less over time if they get bombarded with Subaru commercials. In this sense, experience goods † (or, in our case, “experience prices”) are a more apt analogy than posted prices.

Unfortunately, determining a firm’s optimal strategy for balancing engagement and “experience prices” requires solving a noisy and long-horizon decision problem. This is because most digital services adjust a user’s treatment over time in a targeted fashion (i.e., personalization), and investing in engagement fundamentally requires sustained effort over many interactions and, by extension, strategic long-term planning. Firms must also contend with the fact that they have fewer chances to win over users with low engagement, necessitating a degree of risk management.

Thankfully, there’s a few mathematical tricks that make it easier to reason about how firms behave. Let’s start by formalizing a model for these engagement trade-offs, which we’ll write in the language of content selection.

- At each timestep \(\,t\,\) that a user engages, a platform picks a piece of content \(\,i_{t}\) to show the user. This both provides a revenue \(\,r_{t}\) and impacts user satisfaction \(\,x_{t}\), which we’ll treat as a real number.

- The user engages with probability \(\,f(x_{t})\), a function \(\,f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow [0,1]\) of their satisfaction (similar to the classical demand curve). If the user doesn’t engage, their satisfaction is unchanged, \(\,x_{t} = x_{t-1}\), and there is no revenue \(\,r_{t} = 0\).

- The platform wants to maximize their \(\,\gamma\)-discounted payoff:

\[ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}_{\{i_t, x_t, r_t\}} \Biggl[ \sum_{t=1}^\infty r_t \,\gamma^{\,t-1} \Biggl]. \]

The first useful trick for studying firms in such a model is—instead of working with probabilistic engagement events—let’s pretend that users always engage and instead that the firm’s discount rate is variable. If a user is dissatisfied and engages less, from the perspective of the firm’s expected payoff, it’s equivalent to think of the engagement as being unaffected and the firm’s discount rate as decreasing (or interest rates as increasing). In other words, we can write the platform’s payoff as follows, with re-indexed timesteps \(1', 2', \dots\) that include only when a user does engage:

\[ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}_{\{i_{t}, x_{t}, r_{t}\}} \Biggl[ \sum_{t=1}^\infty r_{t'} \prod_{\tau=2}^t \gamma \Bigl(f(x_{t'}) \;+\; \tfrac{\gamma\,f(x_{t'})(1-f(x_{t'}))}{1 \;-\; \gamma\,(1-f(x_{t'}))}\Bigr) \Biggr]. \]

Because discount rates are nice and convex, we can use this equivalence to show that optimal policies all satisfy a relatively simple, and realistic, structure: they monotonically steer user satisfaction towards some target level (which may depend on the user’s initial satisfaction). This simple structure means, for example, that you can efficiently compute a firm’s optimal policy with dynamic programming. We can even consider an online learning setting where one serves a sequence of \(T\) users with unknown engagement functions \(f_{1}, \dots, f_{T}\) and easily guarantee \(\,(\tfrac{1}{2}, O(\sqrt{T}))\)-approximate regret.

Modified Demand Elasticity

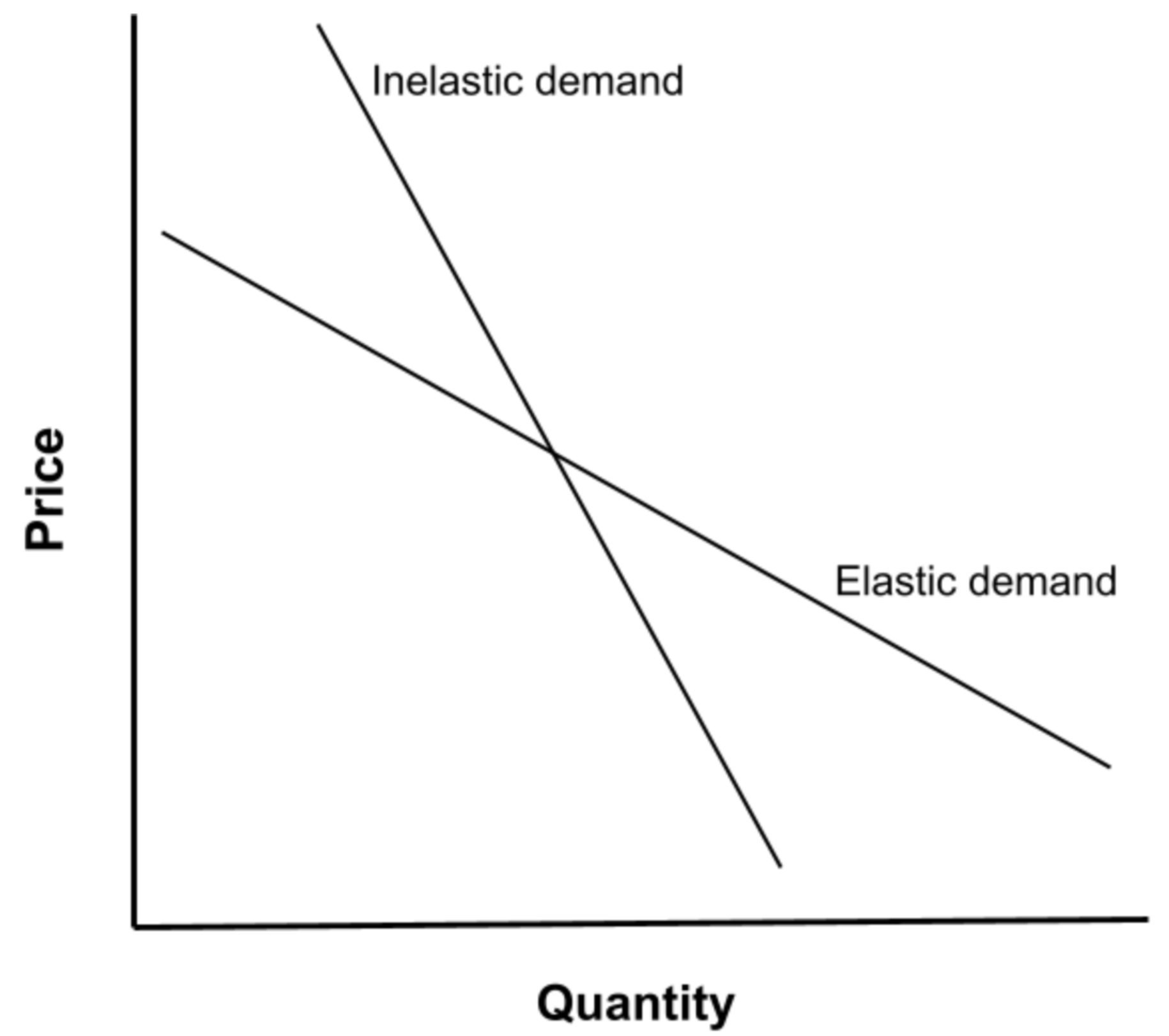

Many classical concepts in pricing theory have analogs that help us understand engagement trade-offs. For example, recall that the classical price-demand trade-off is characterized by the price elasticity of demand \(\,\nabla \log f\), which describes the shape of a demand curve \(\,f\) and the gain in demand that can be realized by a marginal decrease in price. Higher elasticity signals that demand should be more heavily prioritized (at least locally).

However, it’s easy to see that the same demand elasticity \(\,\nabla \log f\) does not provide a complete picture of engagement trade-offs. For example, if a firm’s discount rate is \(\,\gamma = 0\) (they do not care about tomorrow), then no degree of demand elasticity should convince the firm to forego the most myopic profit-maximizing action. This suggests that the correct notion of elasticity should, at a minimum, depend on the firm’s discount rate.

Indeed, we can show that the correct analog of demand elasticity for engagement trade-offs is not the shape of the demand curve \(\,f\) but rather the shape of the variable discount rate:

\[ \text{Modified Elasticity} \;=\; \nabla \log \Bigl( f(x) \;+\; \tfrac{\gamma\,f(x)\,\bigl(1 - f(x)\bigr)}{1 \;-\; \gamma\,\bigl(1 - f(x)\bigr)} \Bigr). \]

I’ll finish off with a particularly neat example of a phenomenon that this elasticity quantity helps surface: an engagement-friction paradox.

Suppose you make it more difficult for a user to re-engage a platform after having previously disengaged. The platform’s revenue is obviously decreased, along with the amount of user engagement that any given platform policy produces. However, user engagement may actually end up increasing. This is simply because friction increases the effective cost of user disengagement and, by extension, increases modified demand elasticity—incentivizing the firm to invest more in engagement.

† Experience goods are economic goods whose value can only be discerned by customers through experience.

References

- Calvano, E., Haghtalab, N., Vitercik, E., & Zhao, E. (2024, February). Algorithmic content selection and the impact of user disengagement. Link.

- Stokel-Walker, C. (2024, August 9). Spotify is full of AI music, and some say it’s ruining the platform. Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/91170296/spotify-ai-music

- Kleinberg, J., Mullainathan, S., & Raghavan, M. (2022, June). The challenge of understanding what users want: Inconsistent preferences and engagement optimization.

Anonymous feedback can be left here. Special thanks to Kunhe Yang and Nivasini Ananthakrishnan for their helpful comments on an early draft of this blog!